“We travel for change” | An Interview with India’s Leading Tiger Conservationist

We met with Dr Raghu Chundawat in the al fresco breeze of our Amala kitchen. He had come to talk about his lodge, the Sarai at Toria, a beautiful and rustic eco-property in Madhya Pradesh, India. But what ended up captivating us was his story, one that spans far beyond his property walls.

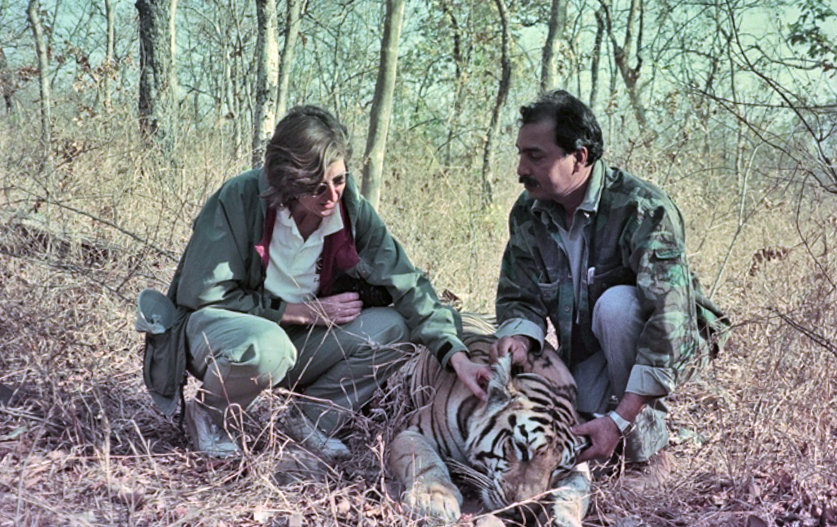

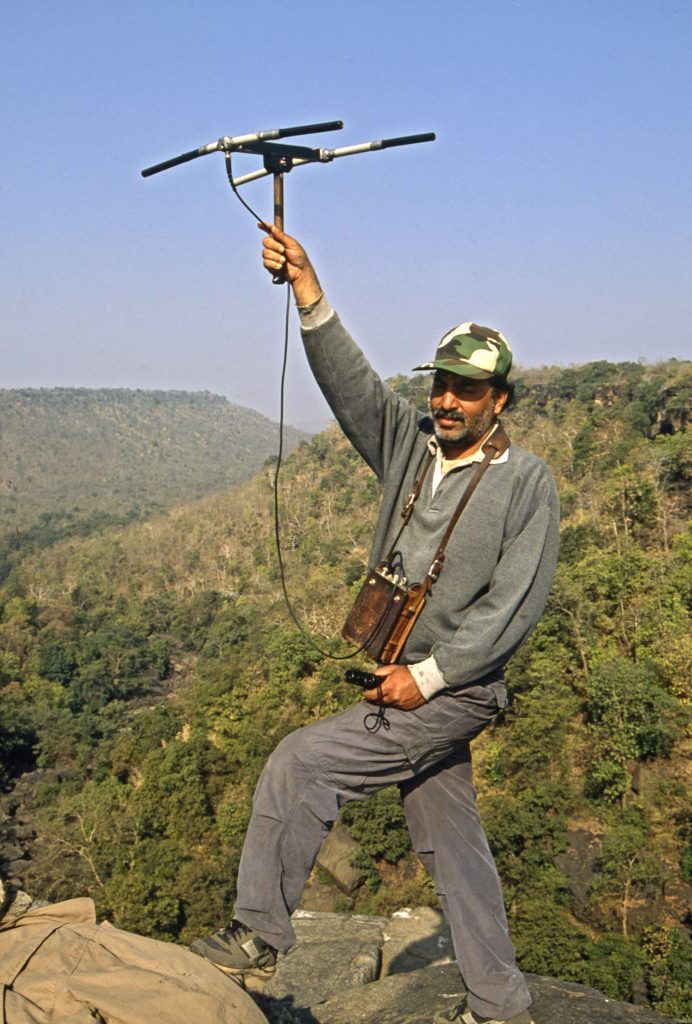

Back in the early 1990s, Dr Raghu had been a pioneer in conservation research on tigers. It was a success story from 1995-2002 but did not last long as the situation changed with a succession in the management leadership. The Panna Tiger Reserve, started to lose tigers – many were found dead along with other animals, and some of the prey species were even seen running loose with snares around their necks. Dr Raghu signalled to authorities that the population of these animals was dwindling and primarily due to illegal poaching, despite the apparent efforts of the Forest Department. The whistleblowing however, was met with contention. Shoot the messenger attitude prevailed and consequently, his tools and equipment were confiscated, and his research permission was rescinded. Still, Dr Raghu continued to speak out, fighting tooth and nail to save these tigers and continuing to petition an intervention. Sadly his warnings were not taken seriously and a few years later in early 2009, there were no tigers left in the Panna Tiger Reserve. Since then, tigers from neighbouring Tiger Reserves have been introduced. This reintroduction has been a great success and now ten years later, Panna once again supports a very healthy tiger population.

While we sat with Dr Raghu and he shared his story, we couldn’t help but wonder – how much work goes into preserving the natural wonders we get to experience in our travels? For one, tigers are notoriously elusive and shy animals, making them hard to track and monitor. They are also extremely territorial and can call home a terrain extending up to 210 square kilometres, not to mention their incredible force and magnitude (one of Panna’s dominant males weighed around 250 kilograms). So how many hours went into preserving the environment of one reserve? How much mapping, setting up of cameras, tracking movements, sitting, waiting, in the heat, in the dark, under rain…?

What was the state of the tiger and leopard population when you began your work?

In 1993/94, I got involved with wild tigers. We saw decline all over India from poaching and the illegal trading of wildlife products, tiger bones and hide. It was really serious. I wanted to find out how we could stop the decline. My research project started in 93/94 first by writing a proposal for funding. The place I decided to do my research work was Panna. We wanted to go where a tiger population was facing threat, and wanted to know what makes it easy for poachers to poach tigers there. We started to monitor tigers by radio-tagging several breeding tigers and noticed that with this intensive monitoring of breeding animals the population started growing. By 2002, it reached its peak, that’s when the film was made.

Together with the BBC and Mike Birkhead, Dr Raghu produced a fascinating documentary about his research in the reserve. “Tigers of the Emerald Forest” gives wonderful insight into the efforts put into studying these majestic creatures.

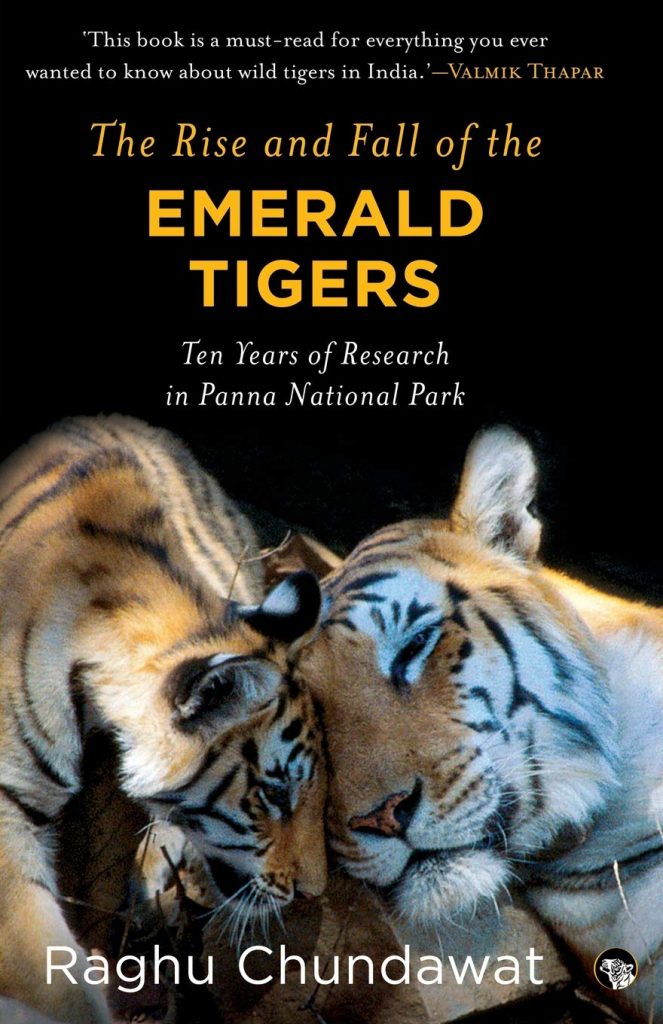

When our research permission was rescinded and monitoring stopped, the tiger population started declining again and by 2009 we lost all the tigers. But after losing all of them, tigers were reintroduced here. It went back to the original numbers so it was a fantastic recovery. Recently my book has come out and talks about the rise and fall of emerald tigers and the numbers going up, and going down and up again. So we’ve learned quite a lot of lessons and it shows that proper monitoring of a population leads to sustaining the population for a long time.

When you say monitoring does that include controlling poaching, supervising, patrolling?

Yes, you see, our Tiger Reserves are like open treasures. For people into illegal trade, the tiger is a valuable thing for them. It’s not something that you can put in a cage and lock up. In India, we don’t perceive the kind of conservation where you put fences around your park. We idealise that it should be natural. You can’t have 200 square kilometres and fence it. So it’s an open treasure. Anybody can come in and that’s the difficulty. India is actually done really well because now we have about 2,500 tigers, this is almost 70% of the world’s wild tiger population. It’s not an easy job. The protection measures are very intense but the success we are able to achieve is because the local population are generally not involved in the poaching. One or two people may get involved. These criminal elements are present in every society. Even in Delhi, we have thieves, we don’t say Delhi people are the thieves. But somehow for poaching, local people are blamed. But that is not the case. The key is to identify those people who are involved in criminal activities and monitor them. It’s crucial.

Have you encountered any major setbacks and challenges?

[Dr Raghu smiles.] Oh, there are so many setbacks, so many challenges. You find the challenge and solve it and there’s a new one. So far India has done well with our protective area network. India now has fifty different tiger reserves. Now the next generation will take advantage of these success stories and build new success stories. Unfortunately a lot of negative stories come out from India, but there are so many positive success stories. If you look at where the success stories are in the world, India would be at the top not only amongst developing countries but developed countries also. What’s happening in India that is noticeable and remarkable is its tiger population. Despite all odds it’s still growing.

So what is one of the more memorable encounters you’ve had with an animal?

When we started monitoring, we collared one female who we called Baavan. That’s what our research team named her because her eyebrows look like the number 52. Baavan in Hindi means 52. It so happened that when we collared her, her first litter was three females and they grew up and we collared them also. And they had cubs. So we had three generations from the Baavan collar. A whole family. Losing them was a really great setback. A couple of her daughters died because of poaching. One of them after she had given birth to three litters was found in a snare and that was really a sad story. But there are so many good memories also. The same individual had several litters and observing mothers nurturing the cubs in the wild is very, very intimate experience.

How does the maintenance of these tigers affect other wildlife? When numbers are down, does it affect other wildlife negatively?

It does because it changes the equilibrium in several ways. The tigers are predators and when their population goes down other predators come in, say; wild dogs. Their focus prey is different. We also have a smaller herbivore called the four-horned antelope, the only animal in the world who has four different horns from the base. It’s found in India and nowhere else. There used to be a good population but once the tigers started disappearing so did they. We have no evidence that it was tiger related but they are coming back with the introduced tiger populations. I think there could be a relationship. So it does make a difference. You have to protect the tigers but also their habitats, their prey, so that the whole ecosystem is protected. Focusing on the welfare of one actually brings in welfare for others, especially in a natural ecosystem.

How do you see the future and your part in continuing in conservation?

For the last ten years I’ve been in the tourism profession. We’ve seen the role it can play in conservation so we’re looking at creating new success stories outside of protected areas. Outside protected areas we have huge potential tiger habitats which are not seeing the benefit of conservation because we haven’t done much work there. That’s where we’re looking at the potential of how we can use tourism to bring in benefits to local communities, for the forests and animals.

So it’s important for you to educate your guests at Sarai about conservation:

Since Joanna (Raghu’s partner, also a naturalist) and I both come from environmental backgrounds, we’ve established the Sarai at Toria, and our lodge is as eco-friendly as possible. Rooms are made entirely from earth, and we don’t have AC in the rooms because it’s not required. The way we’ve designed it, the temperature in the room remains within one degree of change over 24 hours and we are open during fair weather seasons from October to mid-April. We try as much as we can to source locally. When people come to us they really see it and it creates an ambience where you find peace. One of the biggest feedback from our guests has been that during their busy travel in India, for the first time, they find peace sleeping soundly without dogs barking. A luxury feel of 5-star would be out of place for such a rural and natural environment but there’s no compromise on service level or comfort we offer.

How can we, as travel providers, help with these conservation efforts as tourism builds?

Travel agents can play a big role in bringing change. Now my motto is to encourage travel for change. People who travel become catalysts. It’s a very market driven economy. So the local lodge owners will do whatever travel agents and clients like. If they like swimming pools, they make swimming pools. If they like environment friendly structures, they will build them. But you have to talk to them about it. The market can initiate the changes needed to sustain the industry.

As travellers, two sentiments we can indulge are curiosity and respect. The more we know, the more we can understand. Each time we stay near a reserve; each time we go on a game drive into the wilderness to try and spot animals, we might think about the blood, sweat and tears that go into maintaining the life within it. It begins with awareness. We, as consumers, are where the shift begins. When we ask about the history of a hotel, the native culture, or the wildlife living near us, we are connecting to the land. Just like a wild, female tiger became Baavan, the environment can be given a spirit, and recognised as a living, breathing, entity once we learn more about it. Ask about how you can contribute, or how local communities are being impacted. One small step for us can be one big step for Mother Nature.

Because of Dr Raghu’s work, the dwindling tiger population was restored to its original numbers in the late nineties. Much of what we know about tigers in dry forests today is thanks to Dr Raghu and his team, and it was a pleasure hearing him speak so passionately about the intricacies of both politics and nature. It shed honest light on the history of fragile ecosystems and that, when left to their own devices or to monetary intent, can be quickly taken away from us.

You can read more about Dr Raghu and his work in The Rise and Fall of the Emerald Tigers: Ten Years of Research in Panna National Park.

*Parts of this interview have been edited.

Image credits: Joanna Van Gruisen