The Scoop on Hummus

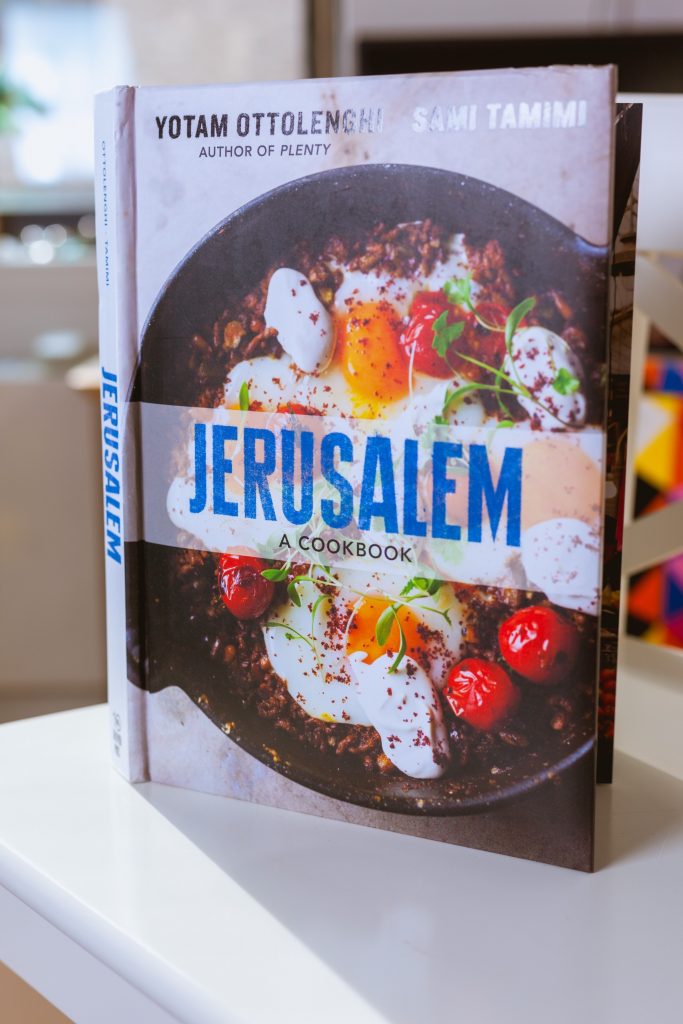

Over the years I’ve collected an array of cookbooks by English-Israeli chef, Yotam Ottolenghi. They burst alive with flavour-packed dishes pulling herbs and spices from Palestine to Malaysia. Dishes like Roasted Chicken With Clementines & Arak and Mee Goreng tell stories of the world, starting and ending at different points. So it’s no wonder that in Jerusalem, the chef highlights, and quite beautifully, the complications that come with tracing the history of some of dishes. He talks about the controversy around “ownership”, using hummus as Exhibit A – a simple dish, but with a complex history. With chickpeas as the main ingredient, the dip/spread/topping has sparked fierce debate between several countries in the Middle East. Israelis call it theirs, the Turks too, and Arabs, with the support that hummus means chickpea in Arabic, also claim it as their own. So who do we have to thank for this exquisite dish?

“these arguments are futile,” write Ottolenghi and his co-author and Palestine-native Sami Tamimi, “Nobody ‘owns’ a dish because it is very likely that someone else cooked it before them and another person before that.” But if we could, to our knowledge, trace back, one story would begin in Egypt around the 13th century where a dish similar to hummus was recorded in cookbooks. Another is rooted in the Hebrew Bible, where a section mentions the dipping of bread in the very similar sounding, “hometz”. While, we can’t deny the parallels, “hometz” also translates to vinegar in modern Hebrew. So again, we are faced with uncertainty. And while we ask ‘where’, we have to ask ‘when’ – at one point, it was all one empire. Some borders didn’t exist until the 1940’s, after years of attempts for certain states like Egypt, Syria and Lebanon claimed independence.

You might ask why this matters, because I did, especially when reading about the Israeli-Lebanese hummus wars. In the late noughties, the president of the Association of Lebanese Industrialists sparked a campaign championing hummus as Lebanese, not Israeli as it had come to be known. After failed attempts at petitioning the EU, as well as suing Israel for copyright infringement, they settled by making 2,000 kilograms of hummus – the world’s largest plate. After Israel retaliated with a satellite dish of the dip weighing 4,000 kilograms, Lebanon took the title back with a mass exceeding 10,000 kilograms. This has yet to be countered.

All this to say, it is not just hummus. It is what represents identity in a world where many find themselves lost or displaced, perhaps straddling a boundary that didn’t used to exist. It is something adored the world over that illustrates creativity and resourcefulness of character. It is a source of pride and belonging. But as much as I see the reasoning behind the dispute, I also boldly celebrate the fact that I am able to enjoy it in so many countries. As a curious traveller, I make it a mission to find local food at every destination. Local food with local flavours and a history of its own.

But after years of travelling to new and old places, one commonality I’ve discovered is ‘crossover foods’. Crossover foods like cross-over music and art and literature. Influence allows incorporation then evolution. And while we can attribute certain dishes to certain destinations, sometimes it’s just a little more complicated. Which is why I like to simplify things when I can, at home, with a handful of ingredients and a good food processor. I heed Ottolenghi’s attitude when he says, “Food is a basic, hedonistic pleasure, a sensual instinct we all share and revel in. It is a shame to spoil it.” To bring some hedonistic pleasure into your home, try our simple hummus recipe here.